We Care About Your Privacy

By clicking “Accept all”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts. View our Privacy Policy.

Many of us have been in a situation where we want to communicate with someone who does not speak the same language. We resort to wild gestures, attempts to say unfamiliar words, grammar seems insignificant and feelings of frustration soar. Some basic vocabulary becomes our lifeline.

Vocabulary is the essence of language. Words hold meaning, and in order to communicate effectively we access relevant vocabulary and express it in a particular manner. Whilst grammar is important, it is possible to convey a very basic message simply by stringing words together. For example, I – dog – see – yesterday. can be understood despite grammatical inaccuracy. Harmer compares the two in the following statement: “If language structures make up the skeleton of language, then it is vocabulary that provides the vital organs and the flesh.” So what vocabulary should we teach and how is it best to teach it?

In contrast to teaching grammar (where there is more consensus in how to progress), teaching vocabulary varies according to the learner requirements. It is most common to start with teaching concrete words such as table or door, and then move onto more abstract words. Two other considerations are word frequency and coverage. Word frequency refers to how often a word is used by the speakers of the language. According to Nation, the first 3,000 high frequency words cover up to 95% of the running words in English, and therefore hold the basic essential knowledge. Out of those 3,000 words, only 170 are function words for grammatical purposes. In addition to looking at the general high frequency of words, we can also consider frequency within a context. For example, there will be a different set of high frequency words in the science classroom than in a social setting.

The key to teaching vocabulary is to provide multiple opportunities to conceptualise, contextualise and define a word. To store new vocabulary in our long term memories, we need to use it by saying it repeatedly in addition to reading it. “Learning new concepts requires active involvement rather than passive definition memorization” (Johnson, 2000). If a new word has been met at least seven times over spaced intervals, there is a good chance that it will be remembered (Thornbury, 2003). There are various approaches to teaching vocabulary which depend on your learner’s level and learning styles. However, all of them require building in spaced repetition which involves recycling and reviewing vocabulary over successive lessons and over a longer period of time.

Teaching vocabulary in context involves teaching thematically. A well established extensive and shared reading programme will allow the learners to consolidate their vocabulary knowledge, and also continuously increase it across a range of contexts.

Where possible, and certainly at very low levels, introduce new vocabulary with the support of realia or images mime, action and gesture. Contrast words such as empty/full to model a concept; these techniques allow learners to visualise and gather understanding of the word. Pronunciation is integral to vocabulary learning. Whenever a new word is taught, the learner must not only listen and read it, but also say it. Teachers should model the sound, show where the stress is and drill the pronunciation allowing the learners to focus on accuracy. Being able to pronounce the word is crucial in activating our memories so we can use it in speech.

At higher levels, breaking a word into components so the learner can use prior knowledge of word stems, prefixes and suffixes or grammatical structure can help with decoding and problem solving.

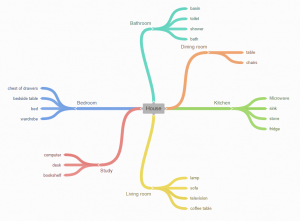

When introducing a new topic, it may be useful to create a word web to categorise the vocabulary. New words can be listed and used as a diagnostic assessment of what the learners already know. Provide all the words in a list and the learners match them to the appropriate branches. Any that are left over or ambiguous can be discussed using concept questions as a form of scaffolding and problem solving. See the example below:

Learning the individual words is the first stage. The next is to use a range of different activities such as crosswords, split dictations and cloze procedures to increase exposure and retain memory. The vocabulary can then be consolidated through extensive reading activities. The final stage of learning involves retrieving the word from memory in order to speak or write it, thus improving future recall.

References

Brazda, J. Context developing activities, //www.teachingenglish.org.uk/thinkvocabulary/context_developing.shtml 19/08/2005

Harmer, J. The Practice of English Language Teaching Fourth Edition. Pearson, 2013

Johnson, D. D. Vocabulary in the elementary and middle school. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon., 2000

Nation, P. The Importance of Vocabulary Size //www.youtube.com/watch?v=UBvcbbt0tg8 2022

Schackne, S. A Common Sense Approach: Vocabulary Building Developing Teachers.com 2006

Thornbury, S. Keeping words on the tip of your…. From Learning English The Guardian Weekly from 24/07/03

I will never forget the ‘feelings’ I experienced during my EAL teacher training, when I sat in a class with a tutor who entered the room with a basket of goodies and greeted us in Swedish. My immediate reaction was one of confusion, which then led to frustration and finally a sense of hopelessness, before I even realised that I was actually expected to experience learning some Swedish without a single word of English allowed in the classroom.

English is a language which has developed over 15 hundred years and has adopted words from over 350 languages. As a result, English has a rich tapestry of vocabulary and spelling patterns which can confuse learners. Having a brief background knowledge of the historical influences on the English language can support our teaching to both first language learners and EAL learners, especially around decoding words when reading.

As school teachers faced with EAL learners in our classrooms, we often push the teaching of phonics down the list, especially at secondary school level. Yet communication is dependent on comprehensive pronunciation when speaking, and on decoding graphemes when reading. Consider for a moment the impact mispronunciation can have on accurate communication. For example, if I ask for soap in a restaurant, I might be faced with a blank stare! This error is caused by confusing two very similar phonemes in soap/soup.