We Care About Your Privacy

By clicking “Accept all”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts. View our Privacy Policy.

Schools often have a number of students who are not yet literate in English. Whilst this includes English-speaking children who are only just learning to read and write, it also covers other groups of learners, including:

'pre-literate' learners who come from an oral language tradition where there is no written form of the language. This can make the concepts of reading and writing very difficult to grasp.

'non-literate' learners who are from literate cultures but have not had opportunities to develop literacy for any one of a number of reasons (Huntley, 1992).

A further group may speak and write in a language that does not use the Roman alphabet. For example, Arabic uses an alphabet where the symbols represent sounds, but it is not a Roman alphabet. Mandarin uses symbols that represent a whole word or idea, rather than separate sounds.

Some learners may need to start with some literacy basics before attempting reading and writing activities in English. Very young learners, typically those aged six to seven years, may not yet be developmentally ready to undertake formal reading and writing, due to limited prior access to education. These learners may need access to the more play-based learning techniques often found in pre-school.

Literacy basics can include holding a pen, copying or drawing shapes and recognising left-to-right and top-to-bottom directionality. It is important not to assume that learners, if shown once, will be able to perform these tasks. It is highly likely that teachers will need to provide many opportunities to practise handwriting. This might include tracing over or copying letters, the first letter or last letters of words, and whole words.

Learners in this situation may have had very little experience with books. Teachers may therefore need to identify for them the front and back of a book, indicate how to turn pages to write on both sides of the paper, explain what margins are used for and describe where to write the date and title of any work. Learners are likely to need lots of help to organise their work as they go along.

"Scaffolding the learning is the process of building up the language by breaking it into chunks and providing support with each chuck in order to move a learner towards independence." (Scott, 2022)

One example of making these connections from speaking and listening to reading and writing is outlined in the following statement by Caroline Scott:

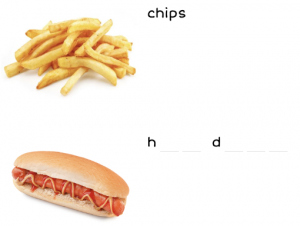

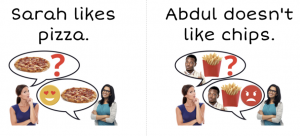

"Teachers can model seeing the image and saying the word to create a connection. They can then move onto identifying the initial letter sound of that word. Then teachers can remove the initial letter sound and ask learners to have a go at writing the initial letter. Then, after significant practice with the identifying initial letter sounds and associated grapheme (written form), teachers can move to teaching the final letter sounds. Of course, teachers will need to be familiar with the English phonemes to do this, as some words are not decodable and others have phonemes that are less obvious, e.g. 'l i k e'. 'L' is the initial letter sound, but the final letter sound is 'i_e', so teachers need to carefully choose the words they will teach the learner to write, in order to scaffold the language construction from speaking and listening through to reading and writing." (Scott, 2022)

A key principle is that oracy - the ability to speak clearly and correctly - should precede any reading or writing activity. It is vital that learners, especially those who have always expressed themselves orally, understand the meaning of the words they are learning.

The use of image-based learning, along with repetition and controlled practice, are key elements to ensure that learners understand the meaning of words.

Flashcard images, such as those used in the Learning Village, can support the communication of concepts. Teachers can use flashcards to provide lots of opportunities to hear and use language.

This oral work allows teachers to hear any pronunciation problems and follow up with work on any problematic phonemes (sounds) or graphemes (written sounds).

After this stage, learners can be supported to read, say and match words and images. Matching activities using words and images can be particularly beneficial - and games such as 'Splat' also work well. In this game, the teacher puts the images and/or words on the table. The teacher says one of the words and the learners compete to be the first to place their hand on the correct image or word. The learner with the most images or words at the end of the round is the winner.

Learners can then start to copy words. Cut words into individual letters for learners to rearrange, or use ready-prepared letters, such as those found in Early Years classrooms, to sequence letters into words. Alternatively, learners can write the word below a model. It is an excellent idea to do this both in English and, if possible, in the learner's home language.

Finally, learners can complete words, having been given the first or other letters of the word.

From word level, teachers can move to sentence level, following the same process.

Needless to say, not all learners will need every stage of scaffolding; teacher judgements about how fast to progress, what to include and what to omit are critical.

Although this group of learners may have very little English, they often have a critical need for document literacy. Learners urgently need to fill out forms, read timetables and understand messages and notes. They therefore need to quickly learn the words they will encounter in these contexts. Focusing on names, days, times and dates, as well as high frequency words, is a good starting point.

You can download a sample literacy scaffolding resource by clicking on the 'Download' buttons at the top or bottom of this article.

References

Alcala, A.L. (2000). The pre-literate student: A framework for developing an effective instructional program. ERIC Digest. College Park, MD: ERIC Clearinghouse on Assessment and Evaluation. (ERIC No. ED 447 148)

Huntley, H. S. (1992). The new illiteracy: A study of the pedagogic principles of teaching English as a second language to non-literate adults (October, 1992 ed.): ERIC.

Teaching in a way that is responsive to the diversity in our classrooms has a huge impact on the learning outcomes of English language learners. Strong school-family relationships, culturally responsive classrooms, and the deliberate use of effective teaching strategies can help English language learners to succeed at school.

March is Women's History Month, an opportunity to study the often overlooked contributions of women throughout history. However, Women’s History Month should be about more than just studying famous women. It provides an opportunity to refine our understanding of history so that it includes women in every aspect of accounts of past lives. Women’s History Month is an opportunity to challenge traditional narratives and really explore women’s contributions to the world.

Assessment in an EAL context takes many forms. It can be formal (e.g. tests and examinations), informal (e.g. teacher observations) or learner self-assessment.