We Care About Your Privacy

By clicking “Accept all”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts. View our Privacy Policy.

Effective assessment for learning (AfL) is ‘informed feedback to pupils about their work’ (Shaw, 1998). As Broadfoot et al (1999) discuss, there are five key ways in which we can enhance learning by assessment. These steps can be universally applied to all learning and all learners, and thus address the learning needs of EAL learners in physical and virtual classrooms. They are:

As we can see, these five key ways to enhance learning are multifaceted and no single teacher can tackle all five alone. There must be a whole-school approach, with teachers working consistently on their whole-school assessment policy, with the aim of providing the best assessment opportunities for their learners. But do educators have enough information about their pupils’ learning to allow them to find the best next steps?

Individual teachers can have a big impact on learning by creating useful AfL opportunities in their own classrooms. Creating a really effective environment for AfL definitely has its challenges, and these can be heightened when providing AfL for learners with EAL.

How can learners have ownership over their own learning, assess themselves and understand how to improve if they have limited proficiency in the language of instruction? Giving learners the tools of AfL can go a long way to improving engagement and empowering learners. Needless to say, it is vitally important for EAL learners to feel included, whatever their stage of English learning.

The following questions focus around heightening involvement in learning for EAL learners.

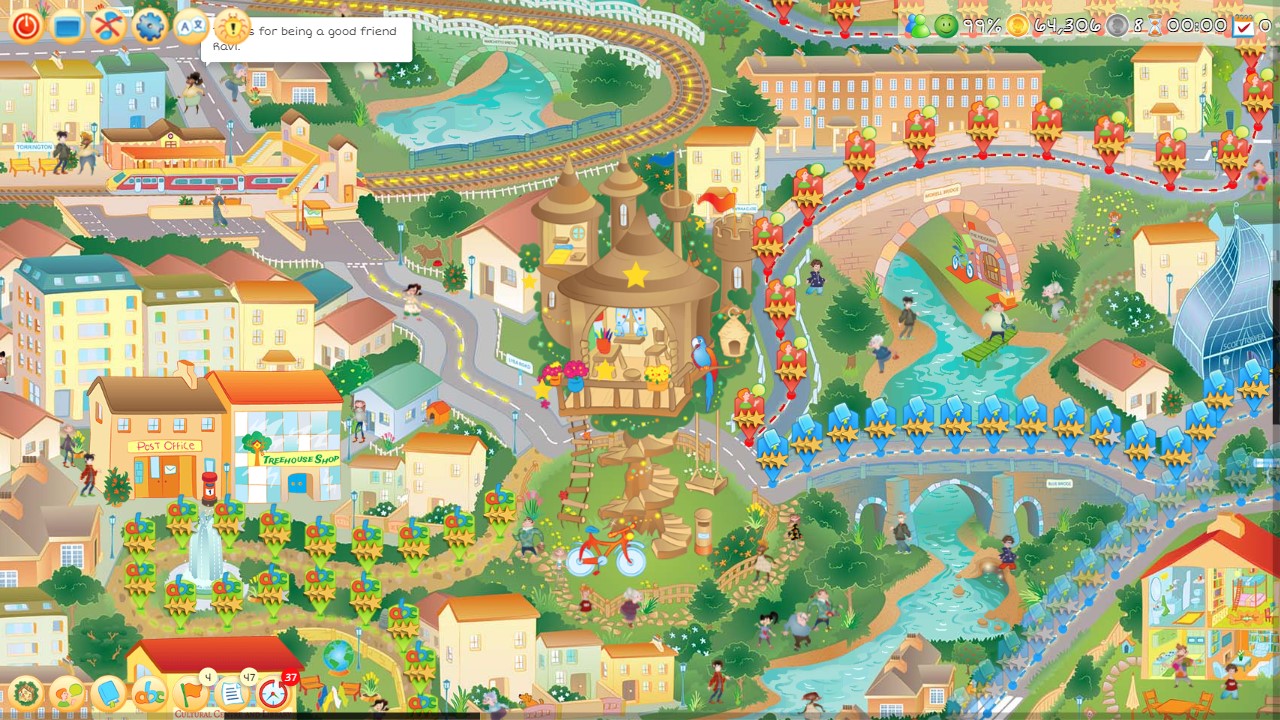

Many EAL teachers use Learning Village to help with the assessment of EAL learners, while other educators make their own resources for assessment. Learning Village is a blended learning platform for EAL teaching and learning. It works through a combination of independent and small-group teaching - using images - and has a range of learning and assessment options, with many tools to support educators and learners in AfL.

Many educators have found Learning Village very supportive, as learners can learn independently on the platform, with educators able to access assessment information to find out key indicators, such as the length of time a learner has spent on each lesson, what they succeeded at and what they need extra practice on. This gives educators crucial information on the next steps for learning.

Learning Village can help empower learners in their own self-assessment through its learning cycle for independent learning: learn-practise-assess. Learners have some leeway as to the pace with which they work through the 'learn' part of each lesson and can choose to move on to the next part of the learning cycle when they feel that they are ready.

Knowing how to improve is knowing what can be done better. Thus, learners must know and understand what they are learning in the first place, which can be a challenge for an EAL learner in a mainstream classroom.

Teachers can provide EAL learners with a number of tools to help support and scaffold their learning. The use of images is important here: giving learners images associated with key language and language structures relating to the lesson can hook the learner into the lesson, providing the learner with a starting point for learning and therefore improvement. Language models are also vital. These could take the form of simple sentences presented in a substitution table, so that learners can demonstrate the variety of alternative vocabulary or language structures they know. Learning Village is based on learning through images and also enables educators to make their own substitution tables.

Furthermore, it can be useful to let learners know about future topics or areas for learning, so that they can participate in topic pre-learning. Educators have found many positives in giving their learners flexibility over their learning timetable - and providing learners with topics to learn at their own pace can be useful. Again, the learner could take ownership of the way in which this occurs.

For instance, pre-learning in their own language could mean that they have a solid understanding of key concepts that they will meet in their future learning, whereas pre-learning in English may mean that they will be familiar with upcoming key vocabulary and language structures. Both pathways lead to the learner feeling more confident and knowledgeable in their lessons. Additionally, learners could have the option of learning their topic content independently, or in small-group teaching and learning situations.

Depending on the language competency of the learner, it may be useful to place them on an individual learning programme, such as Learning Village, where they have ownership over variants such as the pace at which they work, the amount of content they cover in a session, the length of time spent learning and the amount of repetition they require, to name a few.

Other options could be to give learners a choice over the medium in which they work. For instance, if a learner feels more comfortable speaking than writing, could the learner record their ideas/findings/conclusions via audio or video software? To support learners in this, provide language prompts like sentence starters and substitution tables, modelled answers (providing structure and setting standards of expectation) and frames for speaking and writing.

Graphic organisers, provided by the teacher or developed with the learners, enable learners to write or speak to a specific frame. They are useful for supporting the understanding of the text as a whole. Furthermore, learners benefit from paired discussion, preferably in their first language, before beginning written work or work that will be recorded using another medium. This might feel counterintuitive, but researchers such as Cummins (2001) highlight the benefits of EAL learners continuing to learn in their own language alongside English.

Whole schools, educators and families have had to reframe their thinking on what schooling is and looks like in the last decade. Needless to say, parents and carers are more involved in learning, and successes appear to be related to the level of engagement shown by parents, carers and learners. High interest seems to link to greater engagement. Thus, greater ownership over learning should equate to a greater engagement in learning.

AfL has the potential to make a real impact on learning and engagement. A whole-school approach is required to ensure consistency for all, but individual teachers are in a unique position to use AfL to make a difference to the EAL learners in their own classrooms. The key, as ever, is to know your learners, so that you can add value to their learning experience every step of the way.

References

Assessment Reform Group, 2002, Assessment for Learning: 10 principles. Research-based principles to guide classroom practice. London: Assessment Reform Group.

Black, P.J. and William, D., 1998, Assessment and Classroom Learning. Assessment in Education, 5(1), 7-74. Page 5 T.

Broadfoot et al, 1999, Assessment for Learning: Beyond the black box. Cambridge: University of Cambridge School of Education. [Accessed 27 Feb. 2020].

Cummins, J., 2001, Language, Power and Pedagogy: Bilingual pupils in the Crossfire. Clevedon: Avon.

National Curriculum Task Group on Assessment and Testing (TGAT), 1988, A Report. [Accessed 27 Feb 2020].

Shaw, T., 1998, Chief Inspector for Northern Ireland, when launching the School Improvement Plan for Northern Ireland.

Cloze procedures are tasks where learners fill in the blanks in a text from which entire words have been omitted. Learners decide on the most appropriate words to fill the gaps from a bank of provided words. The word 'cloze' (close) is derived from the word 'closure', whereby participants complete a not quite finished pattern or text by inserting or choosing words to give the text closure (Walter, 1974).

Getting behaviour 'right' is crucially important for all schools. Ensuring that we have a 'fit for purpose' behaviour policy that caters for all pupils throughout their schooling - including EAL pupils - is vital for the feel and culture of our schools, as well as for allowing pupils to feel safe and be in the right environment to learn to their full potential.

EAL learning should balance meaning‑focused output, form‑focused instruction, and fluency development to support communicative competence. As educators, we are naturally reflective creatures, habitually revisiting lessons in our minds to see if we could somehow improve. Could the outcomes have been better? Were the discussions rich and high in quality? Was the balance of activities right to get the best possible language learning progression? Here, we will explore how to get the right balance in lessons, as well as suggesting activities.