We Care About Your Privacy

By clicking “Accept all”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts. View our Privacy Policy.

Lea Forest, my school in Birmingham, has been using the Learning Village for over three years. It has proved a highly effective learning and teaching resource, with the children making strong progress. The Learning Village asked us to pilot its newest feature: the Sentence Analyser!

We were seeking a resource that would help us teach the average 75,000 words needed for the children’s language to flourish and to deepen their morphology skills. We thought the Sentence Analyser may be a useful resource.

Over the course of four months, we used the Sentence Analyser in all its various forms. Our previous article 'How do I pilot an edtech learning tool? Piloting the 'Sentence Analyser'' discussed the different ways in which we can use this resource. We reviewed our data and successes with the analyser over the pilot period.

We operate a ‘Hub’ system, in which small groups of EAL children attend intensive learning sessions. These children were selected to be introduced to the Sentence Analyser. Meanwhile, a control group of nine EAL children, already competent in English, was established. This control group did not use the analyser.

At first, the Hub children were wary. They felt that the analyser looked overwhelming and they were not sure how it would help. However, over the course of the autumn term, the children began to enjoy using the resource and could see the benefits it brought in helping them understand words and extend their vocabulary.

A display was created in which expanded noun phrases were introduced to the children, with each word placed under its word class heading. To begin with, the children changed and added words like article determiners, adjectives, nouns, pronouns and verbs. In no time, they were able to produce expanded noun phrases using the key words given, and were then able to move onto producing their own phrases on post it notes. Once the children had acquired an understanding of some word classes and of how to use the display, they could manipulate the sentences and make more complex combinations. For example, they were able to change sentences from the past to the present tense and vice versa, to extend sentences with relative clauses and use subordination of clauses, and to select the most effective synonyms from a wide range. This display thus had an immense impact.

In addition, Sentence Analyser grids were generated on the Learning Village. These supported the children in writing grammatically correct sentences. The picture below shows a sentence grid in which the children needed to select the correct article determiner to describe nouns that had previously been learnt. Intermediate learners were pre-taught adjectives as well. They had to select appropriate adjectives from the grid – more competent learners, meanwhile, had to use their own.

“When collecting data there are three principles that will be considered: what does the data show, how do you know and what are you going to do about it.”

Amanda Spielman (2018), Bryanston Education Summit.

To begin with, it was essential to take an initial assessment of all of the children’s morphology understanding, in order to track their progress and attainment over the course of the pilot.

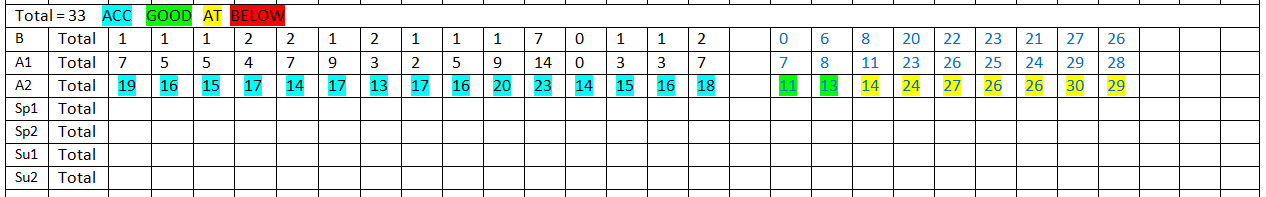

The table above shows the overall scores taken from an assessment designed purposefully to assess aspects of words and sentences: black signifies the children in the EAL Hub and blue the control children. The data shows that the Hub children scored very low on their initial assessment, compared with the control children. However, over the course of the pilot, all of the Hub children made accelerated progress, closing some of the gap with their peers. The control children, meanwhile, made just satisfactory to good progress. This shows that the Hub children’s understanding grew far more quickly.

Not only did the Hub children show accelerated progress on their morphology understanding, they also made good progress through the NASSEA EAL Assessment continuum, as well as becoming more confident in their spoken English, holding more detailed conversations. In addition, the children’s written work evidenced improvements. Through the use of taught vocabulary and sentence structures, the children’s ability to write a specific learnt genre improved.

Using the Sentence Analyser alongside other EAL resources, strategies and first class teaching, the initial data appears positive.

The Sentence Analyser will be introduced to the staff and trailed across the whole school in the spring term. During this period, the staff and children will fill in the pupil and staff voice questionnaires and the children will complete another round of the assessment. This data will be collected and analysed. The impact of the resource will be shared with the staff and ‘what went well’ and ‘even better ifs’ will be discussed before the next steps of further implementation and training take place in the summer term. The final round of data collection will be held at the end of the school year and a decision taken as to whether to embed the resource within the EAL curriculum.

What will the forthcoming data show? What will the staff think? Will the resource be beneficial enough to become embedded? Find out in the next article – June 2019!

You can download the resource accompanying this article by clicking here.

Click here to read part one of this series of articles.

Click here to read part three of this series of articles.

References

Amanda Spielman (2018), Bryanston Education Summit, Saturday, 8th December 2018

Edtech (2015), Pilot Framework, Wednesday, 29th September 2018

There is a plethora of things to consider when piloting a new learning resource or scheme of work, so having a tried and tested framework for testing is helpful. At Lea Forest Academy we follow our piloting framework which was adapted from Edtech (2015), Pilot Framework.

Studies have found that learning a skill yourself, and then applying it, not only brings immense personal satisfaction (among other valuable benefits), but also leads to greater achievement. It’s an important part of an enquiry-based curriculum.

Personal satisfaction can be achieved through learning that is personalised and by promoting a growth mindset. Carol Dweck, professor of psychology at Stanford University, explains simply how achievement and success can be perceived:

In September 2015, Lea Forest Academy took on an additional class of 16 Year 2 newly arrived EAL children. Eight of these children had never been schooled, while eight had had some schooling experience in their home country. The school had no specific EAL provision in place or trained staff.

What did they do?

Where did they start?